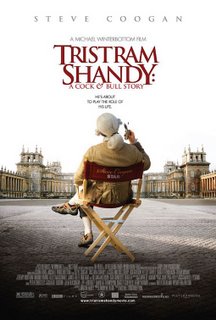

I managed to ameliorate my habit of missing the starting times of movies yesterday, and to break this duck I chose Michael Winterbottom's A Cock and Bull Story, his adaptation of Laurence Sterne's The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, a book I count as one of my favourites, though to be honest I have not read it since I was eighteen (rather like one of the characters in the film). My own memories of it might be coloured by the fact that I was introduced to it and "taught" it by one of the world's foremost Sterne experts, and later his biographer, Ian Campbell Ross, though I do remember laughing a lot and marvelling at its proto-post-modernist (lack of) structure and dissection of time, narrative and its eponymous hero, who gets very little of his life into the five-hundred or so pages.

Before I slip into critical theory jargon, it might be helpful to summarise the book and its author. Sterne was an Anglo-Irish clergyman, born in 1713 and raised in Clonmel, whisked off to an English boarding school at the age of 11, never to return to the South Riding of Tipperary, and he settled into a Church of England post in Yorkshire, a life that formed the background for Shandy, which was published in serial form from 1759 onwards. He wrote but one other novel, A Sentimental Journey, published shortly before his death in 1768. Tristram Shandy concerns the life - narrated in the first person - of its hero, a Yorkshire gentleman, told from the moment of his conception, and it is subject to numerous diversions and asides that prevent his life-story from ever being told; there is far more of Tristram's parents and his Uncle Toby (gravely wounded in the lumber region at the Battle of Namur in 1695, a battle he re-enacts obsessively in his back garden) than there is of the chief protagonist, and, as far as I remember, after five hundred pages, he is only about eight at the close of the novel. As can be gathered from all that the chief matter of the novel is the difficulty of fitting all of life in, the impossibility of editing; it is a bit like those people (we all know one or two) who are incapable of saying in less than five hundred words what can easily be related in fifteen, only more interesting and funnier. It is viewed today as a forerunner to the post-modern novel, but though it does have a light-hearted theoretical underpinning, Shandy is more the product of an age where the novel was not yet respectable, never mind formulated enough for it qualify as an anti-novel, or some such thing. Like Sterne's contemporary Henry Fielding's Tom Jones, this novel probably would have failed to find a publisher at most times in the 200 years following its publication. As it stood, in 1759 it would have been viewed as little more than the eccentric ramblings of an obscure country clergyman, quintessentially English, as the cliché goes.

The novel, like many other structurally tricky ones, has always been described as unfilmable, but there really is no such thing as an unfilmable novel: anything can be adapted for the screen, it is just a question of whether it can be done well. Winterbottom and his regular screenwriter Frank Cottrell Boyce choose the most sensible option, framing it as a film-within-a-film, the shooting of an adaption of the novel. In this sense it is like the adaption of The French Lieutenant's Woman, scripted by Harold Pinter for Karel Reisz, but Winterbottom's film is a lot less dull and even less gimmicky. The book's structure is quickly dispensed with, Steve Coogan (playing himself, as he so often did in his TV stand-up in the 1990s) mutters a few inanities about the book's status as an avatar of post-modernism, and it is clear he has not read it, and we only see twenty minutes at most of the film adaptation of the book itself. In this sense it is more like other films about films, such as Altman's The Player or Truffaut's Day For Night. The film is more about events, characters and actors vying for space in the finished narrative; the script is rewritten and the narrative juggled and reshuffled in ways that will be familiar to anybody that has ever worked on a film, as new characters are written in and new actors hired (such as Gillian Anderson, who jets in to play the Widow Wadman, only to be dismayed as the smallness of her role at the end of the film).

The film's main theme though, above all this, is Coogan, or at least the persona at one remove that he has cultivated over the last ten years. Just as John Cleese will forever be Basil Fawlty, so will Steve Coogan forever be Alan Partridge. In fact it is striking how bad all his other comedy throughout the nineties was compared to Partridge (did anyone, other than cider-addled students, really find Paul and Pauline Calf funny? And as for the Portuguese cabaret star, Tony Ferrino...) In recent years however Coogan has carved out a decent acting career for himself, without fully shaking off the shadow of his Norwich-based alter ego (it's a running joke in this film too). At times he has livened up poor films, such as Jim Jarmusch's Coffee and Cigarettes and, more recently, Sophia Coppola's dreadful Marie Antoinette, where, among the young American actors all at sea in ancien régime taffeta, Coogan was a wry, slightly bemused presence. In this film, Coogan plays on his usual theme of casting himself as an oversensitive, vain, vaguely stupid and untrustworthy character. He is appalled (and terrified) at the prospect of his co-star (or supporting actor, as he calls him) Rob Brydon getting a bigger role than him, which given that Brydon plays Uncle Toby, and Coogan Shandy father and son, is quite feasible. The script then gets rewritten to give Brydon a bigger part and the film rambles off to focus, so to speak, on Coogan's failed romantic shennanigans with his Fassbinder-obsessed assistant Naomie Harris, his nightmares of his literally shrinking stature in the film world and his attempts to deflect a tabloid from dishing the dirt on his one-night fling with a lapdancer. Not all terribly flattering but it is a role that Coogan has long played and played quite well too.

The narrative planes meld with one another, to a point where the actors, in the final scene where they watch the rough cut, are playing themselves playing themselves playing the characters in the novel. A few jokes are thrown in that extend the film's realm beyond the film itself: Coogan is interviewed sycophantically by ex-Factory Records supremo Anthony H. Wilson, whom he played so superbly in Winterbottom's 24-Hour Party People, for what we are told are to be the DVD bonuses, and Coogan and Brydon continue their sparring through the final credits and beyond (it's well worth staying in the cinema for them). While some of the gags are obvious and not all that funny, the overall lightness of touch makes for an entertaining film. Winterbottom is a director who works at a Stakhanovite rate, turning out about two films a year (I still have not seen his previous film The Road to Guantanamo), and while they are not always good, there is a pleasing sense of open-endedness about them that rescues them from self-indulgence and will probably ensure that they date well. I would be interested in finding out what the eminent film critic David Thomson, himself a one-time Sterne biographer, thinks of this film. A long post, I know, but it's hard to fit all of life in.

0 comments:

Post a Comment