There are few filmmakers running on such vapid fumes of past glories as the once-great Martin Scorsese. Not since 1990, and GoodFellas has the diminutive New Yorker made a film that can remotely be called great. Since then he has veered from the perplexingly pointless (The Age of Innocence and The Aviator) to the downright execrable (Dalai Lama love-in Kundun and Gangs of New York); the two decent films he has made in that time were made with the help of previous collaborators and were both thinly-veiled retreads of their earlier projects - Nicolas Pileggi, who wrote GoodFellas returned in 1995 to help with Casino and Paul Schrader, who unlike Scorsese, still makes good films himself, popped up in 1999 to pen Bringing out the Dead, which bore more than a passing resemblance to Taxi Driver. Some of Scorsese's cheerleaders claim that he is a consummate artist, continually revisiting his oeuvre and mining it for motifs, ideas and concepts that enrich the project in hand and his work as a whole. It is typical postmodern chasing of one's own tail, and does not account of the fact that Scorsese, for all his flashy camerawork and narrative brio, is a relatively conservative artist, even at the best of times. And recent years, for him, have not been the best of times. Of course his films are now suddenly shoo-ins for Oscar nominations, but this is only a measure of how he has declined and how the previous edginess of his films has softened like a finely champfered corner on a Victorian staircase.

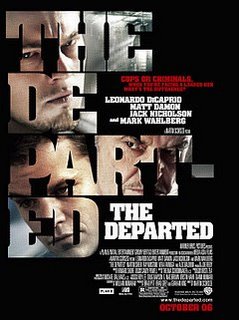

Yet I still go to Scorsese films, if never really expecting much. This years' effort, The Departed is a remake of a good Hong Kong thriller of a few years back, Andrew Lau's Infernal Affairs. Scorsese relocates the tale to Boston, an apt setting for the tale of venality at cross-purposes, in which the local police and the chief ganglord have infiltrated one another. The cop's man inside is Billy Costigan, played by Leonardo di Caprio, starring third time in a row for Marty, while gangster Jack Nicholson's plant is Colin Sullivan, played by Matt Damon.

It is an unusual film in that it vastly improves about halfway through after an initial hour that looks like it might have been directed by Guy Ritchie, so hyperactively annoying is the camerawork - all pans, zooms and close-ups - and there is so much scenery-chewing, particularly among the cops such as Mark Wahlberg's Dignam, and Alec Baldwin's Ellerby that one fears an imminent outbreak of mass onscreen indigestion. Baldwin, whose middle-aged spread has allowed him to effortlessly fill out the high-rent B-movie actor part that he was always destined for is especially laughable and he and Wahlberg both relish spouting the ridiculously macho dialogue that has no doubt been worked over for months by an over-caffeinated screenwriter. The pretentiousness in extremis that is personified by the studio-pic-with-notions is present here in spades: it is a world where hoodlums and ten-year-old urchins alike can quote Joyce and even local boy Nathaniel Hawthorne gets a reference in a supremely irrelevant citation by di Caprio. On top of all this the film is a structural mess for the first half, in sharp contrast to the tightness of Lau's shorter film.

But Scorsese, like a top-flight football side caught napping by weaker opposition, makes a spirited fightback in the second half. When he dispenses with all the flashy trappings and the more intricate, and more superfluous parts of the plot and concentrates on a conventional cops-and-robbers film, it becomes a good deal more watchable. And even gripping, which is laudable enough from my point of view as I already knew roughly how the plot was going to unfold. There is not an awful lot different in this respect from Infernal Affairs, though there is an extra twist at the end that closes off the possibility of a sequel, of which there are now two to the original.

It looks unlikely that Scorsese will ever again hit the heights of his earlier films; in fact so much of his career has now been spent turning out mediocre films one suspects that he may all along have been a mediocre director in disguise, bouyed by a run of a several masterpieces that just happened to be made by him. It may well be that The Color of Money is more representative of him than Raging Bull or The King of Comedy. He has announced that he is leaving Hollywood for his next film, but where he intends to go I do not know as even the independent sector in the US these days is a studio subsidiary. And I think that Hollywood is not really responsible for his decline - if anything it has been exceptionally supportive of him. But Scorsese is still a competent journeyman and he pulls this one out of the fire, after it was shaping up to be possibly his worst yet. The worst thing about this film though, and what lingers most annoyingly long after is the soundtrack. It is simply terrible; not the music itself, which is mostly good, the Stones, Van covering 'Comfortably Numb', Nas, and The Human Beinz's old Northern Soul classic 'Nobody But Me' among others. But Scorsese has been here before; the jukebox is the same for all his films, or at least those set in the late twentieth century. Once again the repetition, the obvious choice of music for a flashback, for a rapidly-summarised rise to fame. Marty doesn't need to slam it home, we know you've made documentaries with Dylan, The Band and one to come with The Stones. Vary the music a bit, even if it means letting Howard Shore do all the soundtrack.

0 comments:

Post a Comment